|

City of Glasgow Glasgow Commercial

Buildings

|

|

Photographs of commercial buildings

of architectural interest in the City of Glasgow

|

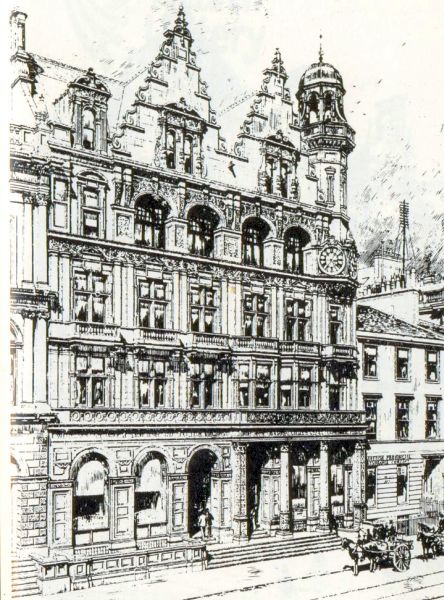

Clydesdale Bank Building in St.Vincent Place |

|

Clydesdale Bank Building |

|

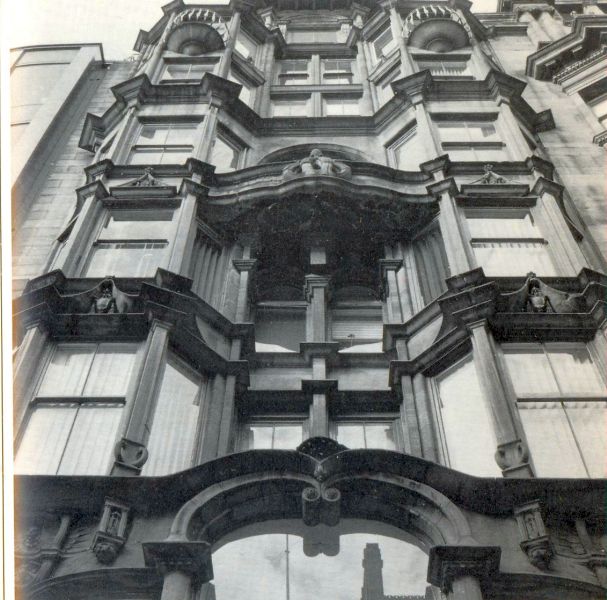

German Renaissance frontage ( c1899-1901 ) of 116 Hope Street |

|

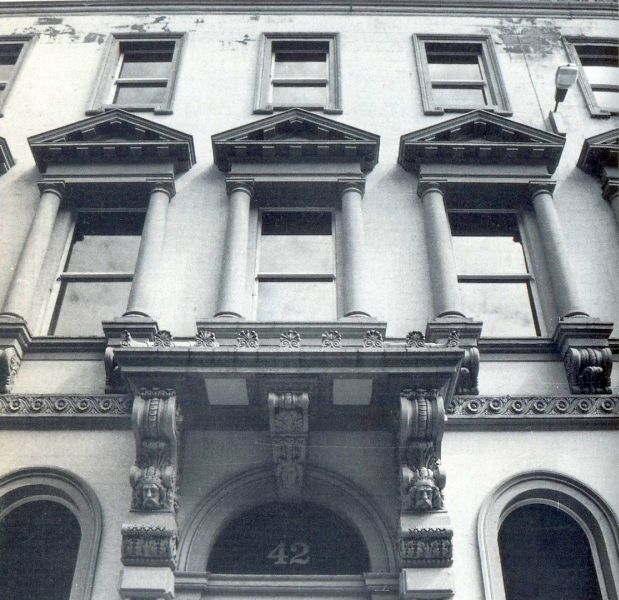

108 Hope Street ( b1893 - 4 )

|

108 HOPE STREET:

For a very upright and sober organisation - one dedicated to the downfall of the demon drink - The Scottish Temperance League certainly choose an exuberant design for their offices.

The League was founded in Glasgow in 1844 and was based initially at 108 Hope Street, which became known as The Scottish Temperance League Offices.

Later use has seen the building occupied by the Daily Record ( converted in 1919 by Keppie & Henderson ) and more recently, The Abbey National.

The offices on the upper floors remain occupied and a shop on the ground floor, a paean to Harry Potter, called The Root of Magic, sells film merchandise, snacks,

drinks and potions.

The building is constructed from red Dumfriesshire sandstone and was designed and built by the architects James Salmon & Son in 1893-4, the design being attributed

to James Gaff Gillespie, a joint recipient, incidentally, along with Charles Rennie Mackintosh, of the Glasgow Institute of Architects Prize in 1889.

Occupying a plot between St Vincent Lane and Renfield Lane, 108 Hope Street, is small in comparison to its neighbours but what it lacks in height, it more than

makes up for in detail.

The building has been described as Flemish Renaissance or Franco-Flemish and its ornamentation has been remarked upon. It has been suggested that a building belonging

to an organisation such as The Temperance League might have gone for a more sombre design. But when have anti-alcohol campaigners been

accused of lacking a sense of fun?

The front elevation has many interesting details; on the ground floor, flanked by engaged Corinthian columns are two tall, arched windows with cherub masks in

the keystones of each arch. Doors at either side of the ground floor windows are topped with corbels and cornices.

On the first floor, sculpted roundels, reminiscent of the Renaissance roundels of Andrea della Robbia, frame a large oriel window.

These are medallions withrelief sculptures of draped, crouching female figures holding discs inscribed with the dates, between which, The League were active in their campaigns.

On the second floor behind a balustrade, there are two long rectangular, centre windows, with stone mullions and transoms.

Very stylised, very long, Corinthian pilasters stretch the full height of the second and third floors, drawing the eye upwards, from the rectangular windows of the

second floor, to the arched windows of the third, both with stone mullions and transom windows.

Two rectangular relief panels with shields, both flanked by winged cherubs, fill the gap between the second and third floor windows. On the left panel there is a lion rampant

and on the right the Glasgow Coat of Arms.

Between the arched windows of the 3rd floor is a roundel showing a protruding female head and below the rectangular windows of the second floor there is another

high-relief sculptural element in the form of a cherub mask, more of which can also be seen on the pilasters.

The fourth floor is an attic, with a two stage Flemish gable frontingonto Hope Street.

This gable end is an elaborate element, with curved stone buttresses which rise to the top of the building.

Within the gable end there is an exceptionally large, central arched window, with stone mullions, transomed as before.

There are three figures, one at the pinnacle, representing Temperance, one on the third floor on the left, representing Fortitude, and one on the right, representing, Faith.

Each holds a Temperance Shield for protection. The figures and all sculptural details were the work of Glasgow sculptor Richard Ferris.

|

James Sellars House ( 1877-1880 ) in West George Street, Glasgow. |

Langside

Hall ( 1845-9 )

Originally the National Bank in Queen Street it was moved stone by stone and reconstructed at Shawlands |

Langside

Halls

at Shawlands Cross |

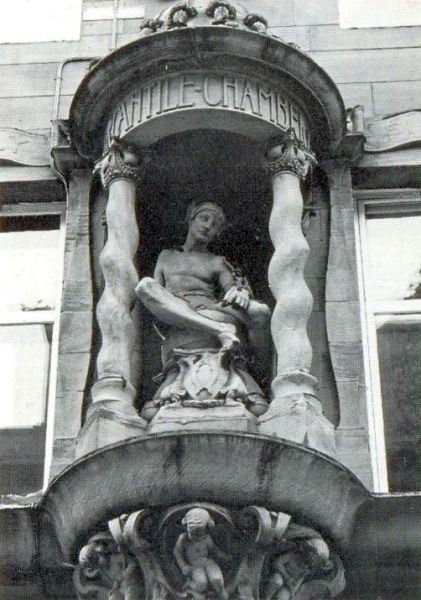

"Mercury"

on the Mercantile Chambers in Bothwell Street, Glasgow |

The

Merchants' House ( 1874-7 )

in West George Street, Glasgow |

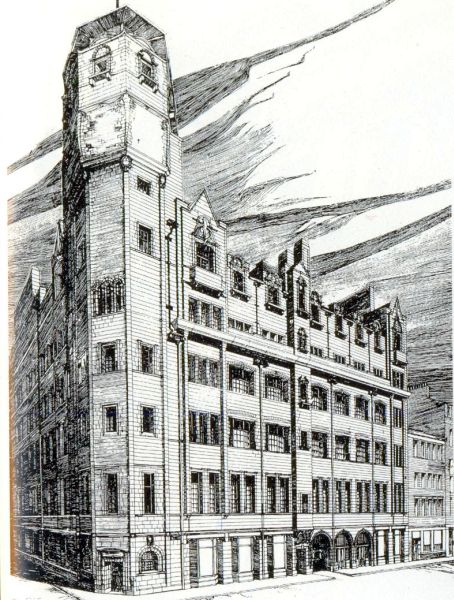

"The

Lighthouse"

60 Mitchell Street ( formerly The Herald offices ) |

The

Lighthouse ( completed 1895 )

Former offices of The Glasgow Herald Now Scotland Centre for Architecture and Design |

The

Lighthouse ( completed 1895 )

Former offices of The Glasgow Herald Now Scotland Centre for Architecture and Design |

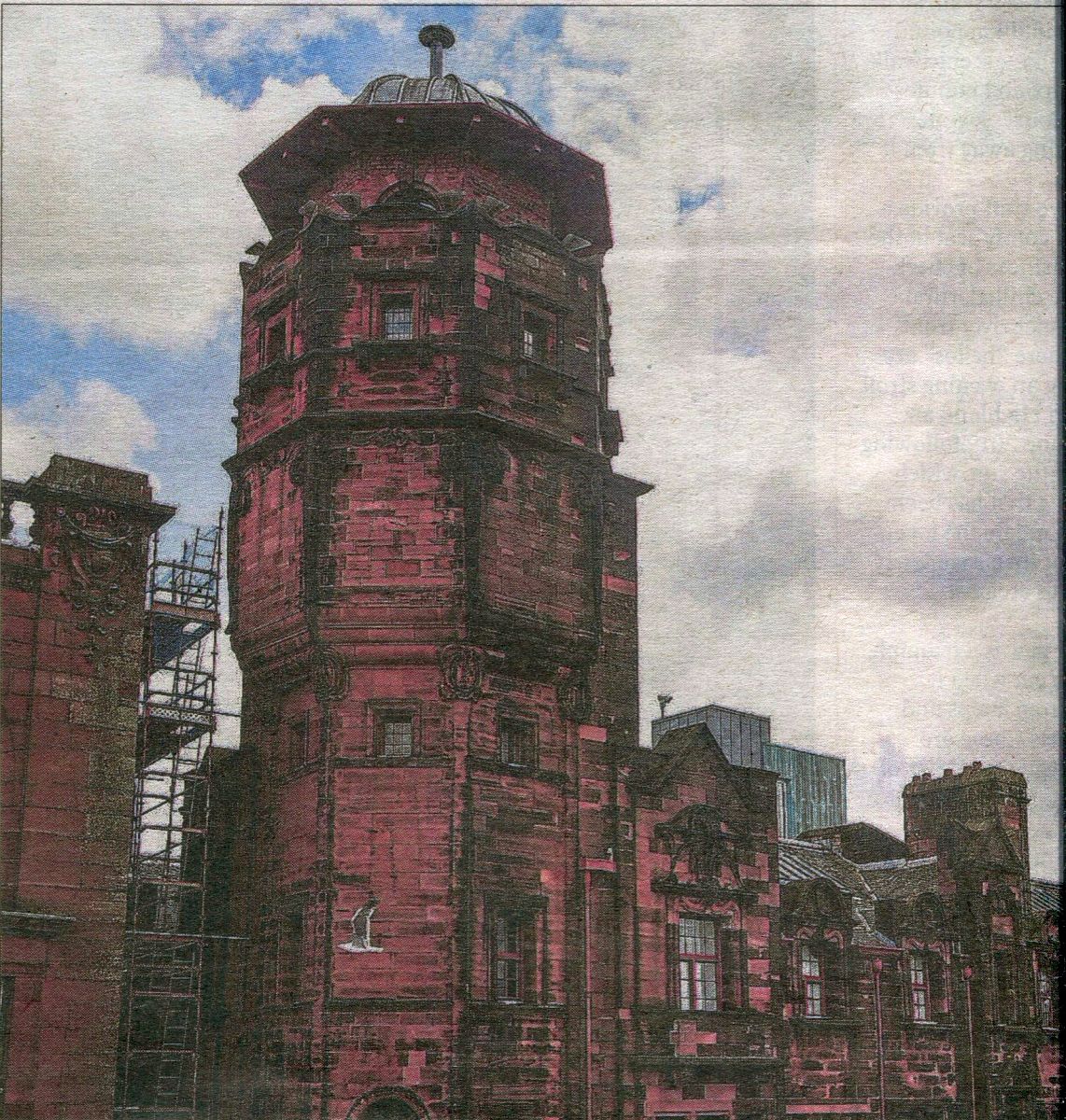

THE LIGHTHOUSE / GLASGOW HERALD BUILDING:

Standing on the corner of Mitchell Street and Mitchell Lane, is the former Glasgow Herald Building, a red sandstone, Category A-Listed building.

It is one of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s first buildings.

The Herald moved to the site in 1880 and originally had a front ofiice on Buchanan Street, with other accommodations leading back to Mitchell Street.

In 1892, a fire in Mitchell Street led to the redevelopment of the site by architects Honeyman & Keppie.

Mackintosh, who was an employee of the firm, is widely believed to have been responsible for the design.

Mackintosh’s later designs are part of The Glasgow Style, a singular variant of Art Nouveau, developed by him and colleagues.

The Herald Building, however, is considered more a mixture , of Renaissance and Gothic architecture with some Art Nouveau details, such as the organic motifs and the embossed

date of construction, which appear on the rainwater hoppers.

With new innovations in construction such as structural steel, the new Glasgow Herald Building in Mitchell Street could be constructed with greater fire safety and with cast-iron columns

supporting the floors, large spaces could be created for the printing presses.

The Herald building presents two elevations to the public, on Mitchell Lane and Mitchell Street.

These external walls were constructed from red sandstone from Locharbriggs, in Dumfries and Galloway, and worked into ashlar, the walls sitting on a granite basement.

At the corner of the building, a tower attached to the building structure reaches upwards to a height of 44.5m / 146ft.

At the top, a water tower designed to hold a 8,000-gallon tank draws the eye, and its corbelled out form dominates the building.

The tower rises upwards on Mitchell Street and provides views across Glasgow which can be experienced by taking the spiral staircase to the top of the tower and the observation deck within.

Behind the tower, attached to the east elevation, is a polygonal brick chimney, which again rises above the roofline to culminate in a castellated turret, with evenly

spaced, recessed, arched windows.

Within the building, there is little ornamentation in the workspaces, however the external facades especially on Mitchell Street present a more interesting display.

The ground floor is punctuated by a mix of large, floor-to ceiling square and arched windows.

Above, each floor has different window sizes in a geometrically consistent and aesthetically pleasing arrangement.

As the building ascends, changing window sizes and protruding elements lead the eye upwards to an almost crenelated silhouette against the sky.

Since being refurbished and re-purposed as Scotland's Centre for Design and Architecture ( completed 1999 ), The Glasgow Herald Building, now known as The Lighthouse, is experiencing a

new level of appreciation.

Its successful redevelopment has saved a part of our architectural heritage and is an example of innovative and apposite conservation.

"Legal

Head"

on the Procurators Library in West George Street in Glasgow |

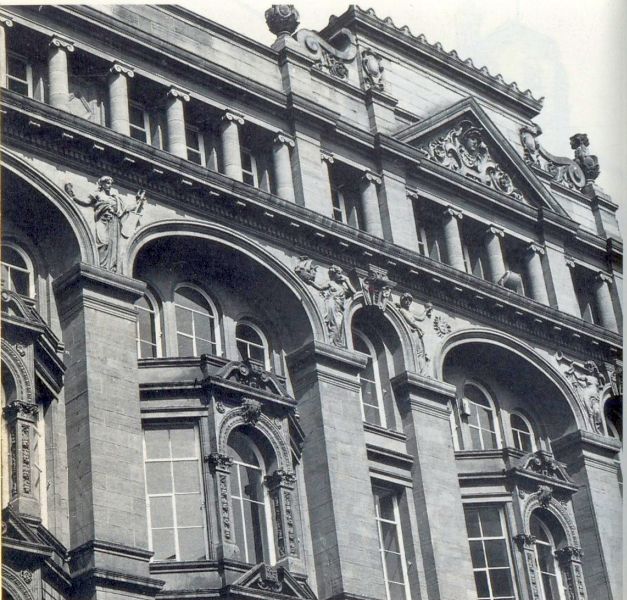

Royal

Bank of Scotland Building ( 1854-7 )

in Gordon Street Originally the HQ of the Commercial Bank |

Savoy

Centre ( 1892-3 )

in Sauchiehall Street Frontage of French-renaissance and "Greek" Thomson influence. |

Stock

Exchange Building

in West George Street Ruskinian Gothic in style Was rebuilt in 1969-71 |

24 St.Vincent Place Franco-Flemish style building |

Art Nouveaux building ( 1899-1901 ) at 144 St.Vincent Street |

French

idiom

Trustee Savings Bank Building in Ingram Street |

Roman

palace style building ( 1866-7 )

at 42 Virginia Street Built for the Glasgow Gas-light company |

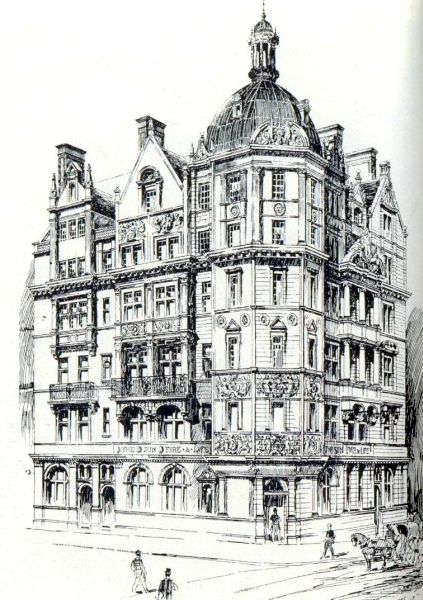

Modern

French style building ( 1892-5 ),

121 West George Street Built for Sun Fire & Life Insurance |

Grand Colosseum Warehoue,

60-68 Jamaica Street |

THE GRAND COLOSSEUM WAREHOUSE

It was a sad end to a building that had been something of a pioneer among department stores in Victorian Glasgow.

The Grand Colosseum Warehouse, which had been established by the peerless entrepreneur Walter Wilson, had a

distinguished lifespan but, by 1994, in the words of the Glasgow Herald, it had become “a beige ruin that sprawls

like a dead elephant, decomposing along Jamaica Street”.

Wilson’s innovations as a retailer saw him create tearooms, decorated with rich Japanese silks, and a ladies-

only saloon, in the store. He gave Glaswegians a taste for Ceylon tea, and when he initiated a delivery

service, facilitated by a Daimler, it was said that crowds used to gather four times a day to watch the

car depart. And one woman who had worked in the Colosseum from aged 15 remembered it as a “beautiful”

store though also as a traditional, regimented employer.

Three blocks of iron-framed warehouses in Jamaica Street, dating from around the 1850s, were in fact

occupied by Wilson’s businesses. The loss of such distinctive buildings has long been lamented; the emporium

itself was demolished in 1994, having latterly been operated by the Paisley’s department store.

Architectural historian Gavin Stamp, writing that year, observed a “shocking hole in the ground” where

Paisley’s had stood, and said that the most handsome and interesting of the city centre’s cast-iron buildings were

the Colosseum blocks. The point is, he added, that Glasgow’s collection of cast-iron buildings was unique in

Britain, symbolic of the city’s remarkable industrial strength in the mid-19th century.

Twenty~nine years later, Michael Pacione, Emeritus Professor of Geography at Strathclyde University

writes that had the Colosseum building survived, it may have been the earliest example of this kind of

construction to be found anywhere.

Regrettably, nothing now remains of this historically important part of Glasgow’s architectural heritage”. A

hotel now stands on the site. Prof Pacione makes the observation in his new book, Glasgow Then and

Now, which traces the history of Glasgow and its occasionally restless pace of change. One absorbing post-

war fact he relates is that fully one-seventh of Scotland’s population was crowded into eight square

kilometres of central Glasgow.

With the aid of then-and-now photographs he has taken over several decades, he goes on to study the scale

of change in distinct areas: 80-plus locations in all, across the city centre, the east end, the north side, the south

side and the West end. He, more than most, is aware that change waits for no-one. As he puts it:

“Did people know that Glasgow had a Colosseum, a Greek temple, and the largest brick building in Europe?

Would they like to see them‘? Too late, they are gone.

“How about the oldest remaining 19th-century bonded warehouse on the Broomielaw, Springburn locomotive works offices,

the first teacher training college in Britain, or former pleasure gardens on the Stobcross estate?

It’s still possible, but people shouldn’t delay in the city, change is a constant.

The pleasure gardens at St Vincent Crescent are an interesting example. In 1849, the Stobcross Estate Company began

speculative building of a new suburb on land just west of Anderston and Finnieston, with the aim of creating a

quality environment to rival that of the nearby terraces on Woodlands Hill. The new street was the first

crescent built in Glasgow to be subdivided into flats rather than individual houses.

For a variety of reasons however, Stobcross Crescent, later renamed St Vincent Crescent, in time succumbed

to slum landlords and to overcrowding, and its decline was such that by the 1950s, demolition

was an option. But interest was expressed in developing the housing in the 1960s; by the 1970s, work had

begun on rehabilitating the street into a desirable residential environment.

“Part of the original pleasure gardens remain in two bowling clubs along the south side of the crescent,”

says Prof Pacione. “However, ironically, given the origins of the suburb, these are under pressure from

modern-day speculative builders.”

As further evidence of the constant nature of change, look no further than the Buchanan Galleries, which

opened only in 1998 but are already the subject of a wide-ranging proposal to demolish them and build in their

place a shopping, residential and office quarter. ( Similar plans are in hand for the St Enoch Centre, which was opened in 1989. )

Archive pictures in the book illustrate the changes that time has visited upon Glasgow. A 2001 picture

of the south-westrcorner of Buchanan Street and Bath Street shows a clutch of elderly buildings occupied by,

amongst other premises, Fingal's pub and the Athene Express restaurant.

Demolishing the properties and building shops, offices and flats on the site was a long and arduous process,

entailing legal hearings. Today the site, across from the Buchanan Galleries, houses such upmarket

shops as Watches of Switzerland.

Also gone are the Macdonald furniture store at the top of North Hanover Street, replaced by a

20-storey, 422-room student accommodation block; and the 1856, ]ohn Burnet-designed Elgin Place

Congregational Church at the corner of Bath Street and Pitt Street. The church’s jet-black, uncleaned

facade made it stand out, even in its latter years when it housed a succession of nightclubs. Severely

damaged by firein 2005, it was demolished, and eventually replaced by the iQ Elgin Place glass tower of

student flats. “The new building stands out from its 19th-century neighbours on Bath Street,” remarks

Prof Pacione, “and is marginally less of an insult to the traditional cityscape that the monstrous office

and apartment buildings opposite on the south side of the street.”

Change in Glasgow came about for many reasons — the need to demolish slums, to house a growing population

to cope with de-industrialisation, to modernise, to improve the transport network — but sometimes the

pressures were external whereas for most of the preceding two centuries Glasgow had been confronted by problems associated

with rapid growth,” Prof Pacione writes, “in the post-war era the city was confronted with challenges of

decline as its traditional manufacturing base succumbed to a changing and more competitive world

economy; “Economic decline was mirrored in the built environment in areas such as the inner east end, where once-grand

warehouses became vacant and fell into disrepair, awaiting a new role in the life of the city.”

Among these warehouses was one on the corner of Bell Street and Watson Street ( the words “T Neale

and Partners, Auctioneers and Valuers” are visible in a 1994 picture ), which was demolished and eventually

replaced by an apartment block. A particularly sad story concerns the Springburn Public Halls. Boasting

an ornate facade ( the work of William B Whitie, who would later design the Mitchell Library), the venue was

opened in 1902 and was for decades the beating heart of Springburn.

Between 1960 and 1985 it operated as a sports centre. After its closure the B-listed building began to deteriorate

Plans to redevelop it came to naught and not even its architectural glories could prevent its demolition in

December 2012. In its place today stands a block of flats.

36 Jamaica

Street

|

Grosvenor

Building ( 1864-5 )

70-80 Gordon Street |

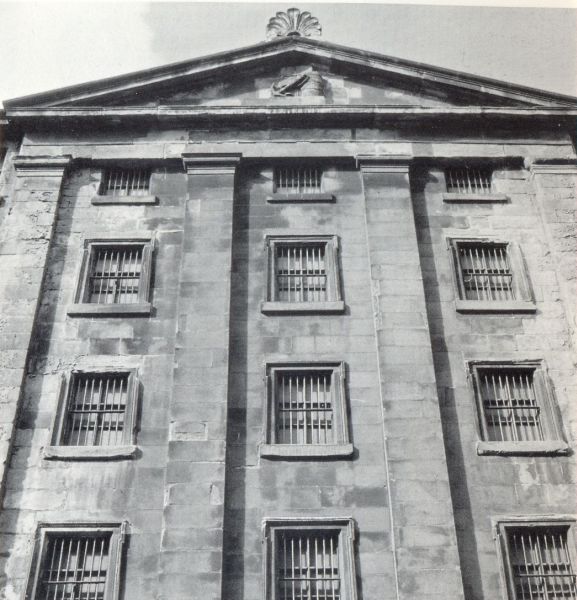

Warehouse

( 1850 - 60s )

in James Watt Street |

Warehouse

( b1869 )

in Boden Street Formerly the Eagle Pottery |

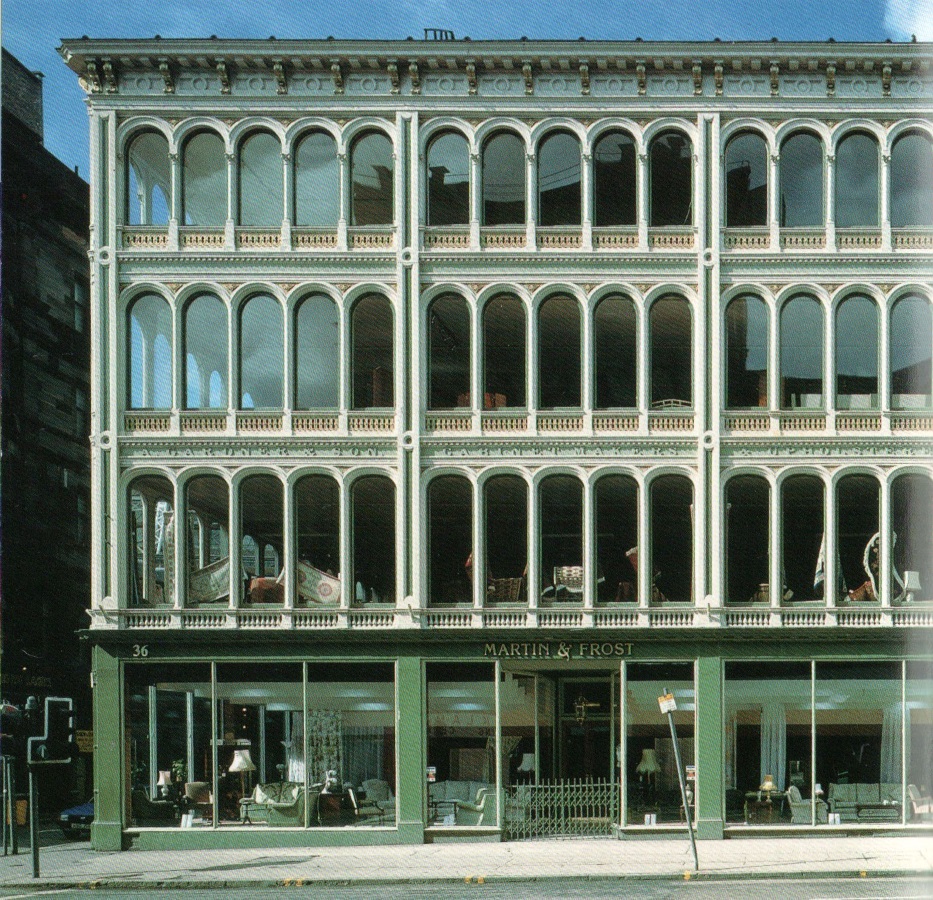

Gardeners

Warehouse

in Jamaica Street This cast-iron fronted building, the oldest in Britain,was originally a furniture warehousefor the upholstery and cabinetmakers A Gardner & Son.The building was constructed in 1856by architect John Baird,although the iron work was designedby ironfounder Robert McConnell. |

Gardeners

Warehouse

in Jamaica Street |

:: Glasgow Buildings

Gallery

:: Glasgow Buildings

Gallery

Glencoe | Ben Nevis | Knoydart | Isle of Skye | Isle of Arran | The West Highland Way

The Eastern Highlands | The Central Highlands | The Southern Highlands | The NW Highlands